Powerset: Premier Public Preview

Foreword: From a Top Blogger

On June 28, 2007 I somehow found myself on a guest list of 35 people, “including top bloggers, top Web 2.0 companies, and members of the press.” We were guests of Powerset, to attend their premier public demonstration of their new natural-language search engine. Being as I must be, a top blogger I took notes on my Web 1.95 T-Mobile Sidekick.

I had previously applied to work at Powerset: where everybody gets a Mac. The offices are located near the Caltrain station, making them a reasonable commute for the Peninsula crowd as well as for those of us accustomed to public transportation. I had interviewed informally with a former colleague, who in sizing me up as a Systems Toolsmith, looked at me with pity when I confessed that my sole capacity for analyzing and expressing complexity is English, and not the formal notation Computer Scientists call “Big O.” (Why must they only hire smart people?)

He did, however, pique my curiosity. “The easy part” of building a new search engine, he had explained, was crawling the entire web. “The hard part,” he went on, was to bring in enough computing capacity to build natural-language indexes. To my ears, Powerset is pushing the envelope of what is feasible, which is cool. And as Google hath shewn, if you can build a better search engine, the world might beat a path to your URL.

Infiltration: Perimeter Security

I found the corporate headquarters on-the-corner-of-Brannan-and-Fourth with only modest difficulty. Powerset had a guest list to get upstairs, but the building security guard informed me that if I was here for the Steelcase party on the ground floor, I should just go right in. Given my duties to the blogosphere, I indulged in a bit of Gonzo Blogulationalism, and crashed the Steelcase party for 25 minutes. Steelcase apparently designs really innovative office furniture that would look right at home in The Container Store. They also had a great spread of tasty Asian dishes, origami kits, and booze. I made sure to tip the bartenders for my Sapporo, and for the Anchor Steam that I pocketed for the journey upstairs to Powerset, where they had not only booze, but special Kool-Aid, and blue pills.

I was among the first to arrive at Powerset. I swiped a handful of Red Pills, and then a handful of Blue Pills, washing them down like candy with my illicit beer. As I waited for the jelly beans to kick in, I found myself chatting with a voluptuous and extremely blond computational linguist with a cool Nordic surname. She was afraid of being misquoted by would-be top bloggers, but I assured her that I am terrible at remembering names, and besides I had been ingesting dubious substances. I got her to admit that she had always approached her work with enthusiasm, but now she felt as if she was working in a company where every last person had great talent and intensity, on a project that she felt could improve the ability of people to search the Internet, and thereby change the world. To a person, the Powerset staff came off as sharp and enthusiastic. It seems that they do drink their own Kool-Aid.

The Powerset lobby quickly became choked with geeks–standards nerds–top bloggers, members of the press–and someone (Powerset) was giving booze to these god-damn animals–and hors d’œuvre! The mushrooms were seriously tasty. Before long, the Beautiful Norse Computational Linguist surprised the milling herd of geeks with a stream of self-confident ejective syllables, and we were ushered into the Powerlabs meeting room, where we took seats, kibitzed, and prepared to be dazzled.

Steve Newcomb, (pronounced “Nuke’m”) the COO, and other Powerset staff introduced themselves. Steve explained the Powerset tradition that every Thursday, at 4:20, all Powerset staff gather in the room where we were now assembled, and are invited to ask questions. The only rule on these occasions is that Steve has to give some sort of answer. It is in this spirit of openness that Powerset sought to present their technology to us.

History of Search and Why We Love Google

About a decade ago, when I wanted to find something on the web, I had two ways to do it. If I was after a well-known topic, I could look it up in Yahoo!‘s directory, which was akin to a Yellow Pages of the Internet. If that didn’t work, there was AltaVista, which had crawled the entire Internet and indexed all the words. I could throw some words at AltaVista and it would give me a list of web pages that matched. AltaVista was great because it knew about every web page and could usually find at least a few pages that matched very obscure topics. Unfortunately, for better-known topics, AltaVista would return a huge, seemingly random laundry-list of pages that matched, and it took some sifting to figure out which pages were the most relevant and interesting. For the majority of topics that ranked between well known and obscure, it was hard to find the best web pages.

Then, around 2000, my friends tipped me off to this new web site: Google, which was a search engine like AltaVista, except that it did well at listing pages in order of relevance. Google had not yet crawled the entire Internet–it was still in beta–but it was so good at search that I would check Google first, then fall back to AltaVista when I couldn’t find what I wanted within Google’s index.

Google’s secret sauce is an algorithm developed by its founders while they were grad students at Stanford: PageRank looks at an index of web pages, and makes a guess as to a web page’s importance based on the importance of pages that link to that page. The importance of those pages is in turn determined by the importance of the pages that link to them, and so forth. So, Google like to hire really smart people who can express and refine such complicated ideas in the form of computer algorithms.

The other really clever thing that Google did to ensure their success, was to have the guts to buck the popular trend of the day: instead of spending a lot of time, money, energy, and web design on making themselves into a catch-all “portal” that would be the ultimate starting page for people “surfing” the world-wide-web, they would focus on search. Since many people start their web browsing at a search engine, these folks began their web browsing at the best search engine. Google have since added other services to keep you in their evil clutches, but their home page, to this day, remains uncluttered and centered around the search box.

Since that time, the major portals have each gone to the great trouble of building search engines that evaluate relevance, as Google does. Since Google beat them to the punch, all of us users who have become used to Google stick with the winner. And when we need to look at maps, or check our e-mail, we tend to chose Google’s offerings, since we’re already using Google and are impressed with their search engine. We love Google!

But, a decade ago, we loved AltaVista.

Natural Language Search

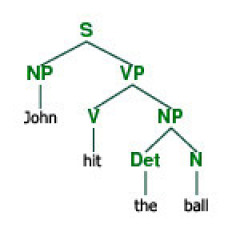

Powerset is working with a technology called “natural language”. When Powerset crawls the Internet, it isn’t merely indexing which words and in what order: it tries to read and understand the words in much the same way that you are reading and hopefully understanding this sentence. In order to do this, it first needs a sufficient understanding of human language to parse the sentences in to their nouns, verbs, adjectives, compounds, et cetera. If you ever diagrammed sentences in grammar school, then you understand the basics of parsing. Once it has parsed a sentence, it must next draw the logical connections revealed by the sentence: what did he know and when did he know it? (and who are we talking about anyway?)

The computers are doing this, and they are doing it for these bizarre human organisms in their thoroughly weird and twisted monkey-jabber human languages, describing ideas and thoughts that are thoroughly beyond a computer’s experience of the world. Powerset’s algorithm has never seen the color blue, but it can know that blue is a color, that the Ocean is blue, that blue is a “cool” color, that The Blues is a form of music related to Jazz . . . it can know a good deal about love, based on the Wikipedia entry . . . but don’t expect a Valentine’s Day e-card.

Since natural language is very difficult, and therefor very interesting, really smart computational linguists have been working on this for a very long time. Powerset have been able to get a head start on the process by licensing technology from Xerox PARC. Who are Xerox PARC? The Palo Alto Research Corporation employs a bunch of geniuses that have been working on advanced technologies for decades. In 1973, they built a personal computer with a graphical interface, controlled by a mouse, with a WYSIWYG document editor. It was another ten years before Apple managed to ship the Lisa, for a modest $10,000 . . . the DOS version of WordPerfect had a WYSIWYG preview feature as early as 1989. That’s just to say that PARC are good at developing technologies that are way ahead of their time.

And in what way is natural language ahead of its time? Well, assuming you can program a computer to do a reasonable job of parsing human language, it still takes a whole lot of CPU “brain power” for a computer to get the job done. During the demo, Powerset explained that a few years ago, it would have taken a few minutes to parse a sentence. They estimated that they couldn’t successfully build a natural language web index unless they could get that down to 3-4 seconds. They explained that their current crawler can parse a sentence in one second, and that they have ever-faster hardware on the way. “Moore’s Law is on our side.”

Powerset are gambling that right now is the time to build a natural-language index of the web.

The Demo: Sufficiently Awesome?

After much ado, the lights went down, and a white box appeared on the screen:

Who acquired Peoplesoft?

The results appeared: Powerset on the left, Google on the right; a list of web pages with short excerpts of matching text. Both correct answers, “but on the left, you see who is highlighted: Oracle corporation announces a merger deal to acquire PeopleSoft . . .

Who did Peoplesoft acquire?

Powerset understands that there is a relationship here: Peoplesoft, which is a software company, acquired, or merged with, bought out, or whatever . . . whom? A company of some sort? The result on the left was a list of articles, each matching a different acquisition target: excerpts highlighted the matching verb phrase and displayed the name of the target company in bold. On the right, Google sat rocking quietly, its knees hugged to its chest, randomly chanting the keywords and offering a great many web pages that didn’t match the search criteria. I could see a bit of drool running down its cheek.

Acquisitions by Peoplesoft

Acquisitions in 2001

“We read every sentence! . . . We parse every sentence! . . . Abstractions! . . . when queried, we look at semantics! See, the answers are in 2001? Google is ‘2001’ and ‘acquisitions’ . . . Google doesn’t understand these tight linguistics.”

Of course, most searches these days are keyword searches: this is what we are used to and I honestly don’t know if we would start asking more sophisticated questions until we have the ability to ask. It was explained that the Powerset engine falls back to keyword searching.

What about spam? You can generate a lot of perfectly valid bogus English using computers, and search engines are constantly wrestling with this. Powerset’s crawler will have the advantage of a semantic understanding, better able to evaluate whether text actually makes any sense or not.

Could you provide a semantics API to guess at spammyness? (Such a service might make it easier to filter e-mail.) Powerset could build a widget that indicates what parts of your blog parse well . . .

What about PageRank? It was explained that page ranking is on the way, “but if you look: our answers are actually correct. We didn’t cover the top companies, but we did cover acquisitions in 2001.” (I like to think that, since they want to filter spam, that writing quality, based on parseability, will become a factor in evaluating relevance.)

There was talk of ontologies, which are descriptions of relationships between things, which make natural language parsing more effective. Powerset are currently using Freebase, Wordnet, and others. “We can import ontologies.” (Wordnet is basically a really sophisticated dictionary and thesaurus that can help a computer understand language. For example, ask Wordnet what it knows of “acquire”. )

There was a quick demonstration of built-in feedback. When asked senators who wrote a book Powerset returned John Kerry, Barack Obama . . . and a “Dr. C K Sen” . . . upon hovering over that result a thumbs up / thumbs down icon appeared, and the result was voted down, not unlike flagging an ad on Craigslist.

So . . . couldn’t Google simply start offering search results that connect with synonyms? They could, and in some cases they do . . . who acquired Peoplesoft could understand that a merger is an acquisition . . . but it still wouldn’t understand relationships. You still wouldn’t get to who did Peoplesoft acquire and the rest. Powerset are confident that, given three decades of refinement at PARC, their parsing technology is more robust than anything their competitors will be able to build quickly.

So, was it awesome? Well, as a top blogger, I was certainly impressed. I am a computer geek with an English degree who dabbled in Linguistics in college: of course I think this is awesome! But did I feel the Earth move? Did it knock my socks off? Did I feel like I was witnessing the next big thing?

No. *

Well . . . not quite . . . maybe . . . not necessarily . . .

[*] Not yet.

This is how I would paraphrase and explain Powerset’s challenge:

“We could throw open the floodgates to the public, but the path of natural language search is littered with the bodies of past failures, and unless it is flamingly obvious that we are better, we’ll flop.

We need to figure out and then illustrate what we are better at . . .”

What Else Could be Awesome?

Let us say you wanted to build a better search engine, so that the world might beat a path to your URL. At some point you have to explain what you mean by “better” . . . better than . . . ? Well, better than Google. You have to build something better than Google. That is hard, because Google is the best search engine and we love Google and Google is really powerful and if you mess with them they might fight dirty and you’ll go home broke and bitter.

You would have to start with a better search engine, and you would have to ask yourself “well, what else could we do better than Google?”

Well, what don’t you like about Google? What could Google do better? (Have you tried telling Google?)

At Powerset, the top “do better” item offered is transparency. Google has a few corporate blogs, but for the most part Google are secretive like Dick Cheney. Details of PageRank? Nope. How many servers and where? None of your business! That is reasonable, sure, but then you see a project that has been sitting around in Google Labs and it doesn’t seem to actually be doing anything. Wouldn’t it be nice to know more?

And, when it comes to things sitting around and people not knowing . . . Google loves to release new things to the public, with the caveat that they are Beta. Beta? Yes, for (at least) three years: Beta! Being a Google addict, I use a lot of Beta services. I find bugs and I certainly have some feedback that my Google colleagues think is valid. And, back to that transparency thing: I have so often found that contacting Google is a serious pain in the butt: you must find the right help site within Google, then you must navigate the help system to the feedback portion, and convince Google that your question or bug report is not already answered, and eventually you will arrive at some or another form that you can fill out, and explain yourself. This data will be filed off in the Googleplex, and somewhere between two days and five months later, you’ll get an e-mail back from a harried temp who has skimmed your inquiry and sent back the appropriate canned response. If there is no appropriate canned response, you’ll hear nothing. As best I can tell, Google’s engineers are too busy interviewing engineering candidates to be further troubled with technical support escalation, feedback, feature requests, or bug reports from anyone with less-than-cafeteria access.

As a characteristic example: Gmail. When Gmail was released to the public in April, 2004, it was mind-blowing: 1GB of mail storage! Awesome! Google has brought you a data mining utopia: you will never have to delete a message again! Ever! Seriously! We’ll let you delete a message if you really want to, but you’ll have to do that in a sub-menu. (Data wants to live, dammit! Forever!)

Apparently, though, the human beings who took to using Gmail felt that deleting messages is a really important feature. Within two months, some users took matters into their own hands and released a Firefox extension to add a delete button to Gmail. In January, 2006, merely 21 months after Gmail’s initial launch, Google added a delete button to the interface. (Hey, at least it took less than two years. That might be faster than Microsoft.

To be sure, while Google has some annoying shortcomings, these flaws are far from horrible. Powerset staff wanted to clarify, for the record, that they never said they wanted to be “Google Killers” . . .

But if you could build a better Google, it would probably be more candid as to what it was doing and why. A better Google would listen to its users, solicit feedback, and incorporate good ideas more rapidly.

Powerlabs: Future Crucible of Awesome

So, just as Google built a better search engine, and coupled their technology with a strategy that centered around making the user happy, Powerset seek to build an even better search engine, and couple this technology with a better strategy around making the user happy.

Before bringing their search engine live to the public, Powerset plan to shepherd new products through a process they call “Powerlabs.” Powerlabs is expected to go live in September, with various search applications going live within nine months of their testing and refinement within Powerlabs.

Powerset explain Powerlabs as a combination of other good ideas:

First, and most obviously, a showcase for applications still-in-development. “Like Google Labs!“

Next, a mechanism for users to preview works-in-progress, submit ideas and bug reports, vote said ideas up and down, and hear back from Powerset developers. “Sort of like Digg.”

Next, “a lot like Facebook,” a social network with API access, where users can hack up and share their own ideas.

A fourth aspect, that seems to be a newer idea for Powerlabs, that borrows from RPGs like World of Warcraft, or the “Yelp Elite” program, is that users will be given opportunities to “level up” and earn additional access and perks within certain areas.

The demo glossed past the probably-not-much-there-yet Powerlabs itself: they skipped to a little widgety thing that they used some months back to impress the Venture Capitalists: The Entertaininator. Given that I am a top blogger, I kinda flaked out when they started talking about old media. I recall a bunch of movie icons spinning around in a circle, then you could click on one, and a bunch of actor’s faces would spin around the movie, and you could click on an actor, and a bunch of movies would spin around the actor, “you could do this forever,” I recall the guy saying.

And then they skipped to the “guess the movie quote” widget in the thingy, and typed in “you can be my wingman” . . . audience? Do you know which actor?

. . .

“Ice man?”

Up popped a headshot and bio of Val Kilmer.

“You could make a lot of money putting this in bars.”

“Just a quick mashup!”

“But think how this could be great for mobile.”

The point? That Powerset is smart enough to parse IMDB and other sources to such a point that one can easily whip up an application that can match a movie quote to a character to an actor, and match actors to movies.

The Verdict? Stay Tuned . . .

So, beyond a smarter vanilla search box, Powerset is hoping to have a bunch of jaw-droppingly cool stuff that gets developed in close coordination with a user community who should feel extremely passionate about applications that they helped build–either by providing useful feedback and bug reports, having built their own application, or having championed something new and awesome.

With Powerlabs, they are assembling an array of new and succeeding “Web 2.0” ideas into a new combination.

I figure we have seen the pieces work in other places. This new combination is so potentially cool, that I really hope it works.

And, of course, it could flop.

They have a very smart and passionate team, they have very impressive technology, they have what sounds like enough cash for the next year. They will need to execute well, they will need to get a lot of newish things right, and they will need to be nimble enough to recover from their mistakes.

And, they’ll need some good luck. Good press. They’ll need to capture users and win their loyalty before others steal their mojo.

Powerlabs is due in September. You should sign up and see for yourself.

Comment

Tiny Print:

<a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>